8 product lessons we can learn from Google+

The reshuffles in management in Google+ recently attracted a lot of press comment and speculation. I thought it an appropriate time to look back on the last couple of years and see what broader product lessons we can learn from the inception, launch and evolution of Google+.

Note that whilst I worked on the original Google+ team and invented the ideas behind Circles, I have long since left, and have no insider knowledge about what is happening, nor does this post have any confidential information. I’m simply sharing what I think are clear product lessons that may help many of us build better things, all of which can be deduced from public information.

1. Build around people problems, not company problems

A dominant theme in the discussion of what is happening with Google+ has been a focus on the problems Google faced with the rise of Facebook, and whether those problems still exist now. Everything I have read in the past few weeks discusses this from a company problem point of view. There has been little discussion on which problems Google+ should or could solve for people, or what new inventions they could build to make people’s lives better. Contrast this with other parts of Google, where clear problems that people have are being solved. If Google+ wants to see engagement numbers similar to Facebook, it needs to focus on how Google+ makes people’s lives markedly better. The vast majority of people don’t care about Google’s problems. Likewise, they don’t use Facebook in order to collect data about themselves so they can be targeted with better advertising. They simply want better tools to help them live a more fulfilling and happier life, and often they can’t foresee tools they will later come to value.

The point here is that social software is not done. Do people want better ways to build, maintain and grow relationships? Of course. Better ways to share their experiences with the people they care about no matter where they are? Of course. None of these problems are solved. People don’t even yet know how they will share experiences in the future; this is why the Facebook acquisition of Oculus Rift is so interesting. Large parts of Google+ don’t offer anything beyond what exists elsewhere.

There is so much room for invention, so much opportunity to make people’s lives better, the Internet is in its infancy. There is no need to worry so deeply about competitive threats, as if it is a zero sum game and there is a foregone product conclusion.

2. Perceived benefits need to be greater than perceived effort

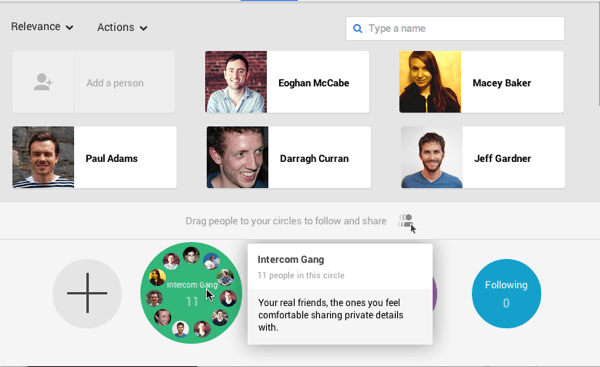

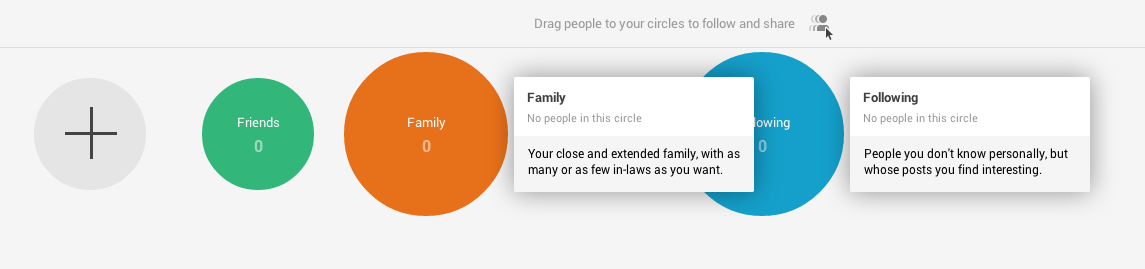

My mobile phone’s address book is full of people I don’t recognise. It is a pretty comprehensive list of all the people in my life, yet woefully managed. One of the most personal parts of my most personal device is full of strangers. This is the same for almost everyone and the reason is simple: it’s not worth the effort to keep it up to date. This is the problem with Google Circles.

The perceived benefit was clear to everyone. Circles more clearly mapped to how life works offline, where people typically share different parts of their life with different groups of people. It was a clear Achilles heel for Facebook at the time, as Facebook’s primary design pattern was to share everything with all your friends, which limited what people were comfortable sharing.

But this is a very hard design problem, and identifying a clear user benefit alone isn’t enough. Execution is as important as initial insight or unique value proposition. Looking at most mobile phone address books indicated people would not manually put their friends into Circles, and more importantly, that they wouldn’t keep them up to date. Circles requires ongoing manual work, and despite the perceived value, it’s simply not worth the effort. It doesn’t matter how beautiful the UI is, how polished the transitions and animations are, how much fun has been added to the experience, people will simply not do it because the perceived effort outweighs the perceived value.

Personally I don’t think this can be fixed. Circles as a literal interpretation, and manual execution, of how real life social networks work will not succeed. It’s time for a rethink, but more on that later.

3. Ruthlessly focus and descope, be patient, the Internet is young

We have a very big, broad mission at Intercom and aspire to build something that is used by millions of apps and billions of people. But we know that if we are successful, this will take many years. Other than incredibly rare outliers like Instagram, social networks take a long time to build out and deepen, just as real life relationships do. This requires patience and deliberate focus. It’s too easy to chase too many things.

Google+ tried to be everything, all at once. As well as the rise of Facebook, there was the growth of Twitter, and Google+ attempted to compete with both. Facebook and Twitter are very different products and often serve independent needs for people. The product complexity within Google+, and the lack of aggressively killing off features people don’t use, suggests that this remains an issue.

This lack of focus adds huge complexity to the product, and huge cognitive effort on the parts of users, therefore increasing the effort required. All of the massively successful social products of the last few years have started out by doing one thing really well, then growing organically and expanding.

4. Embrace the idea that life is messy

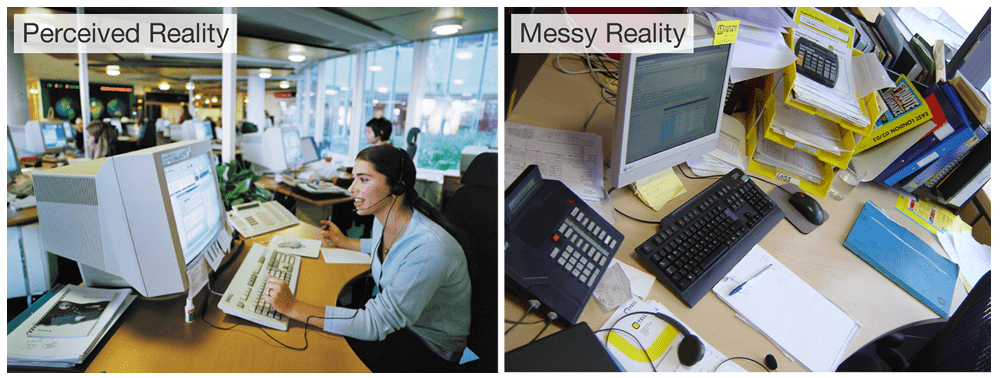

I once did a large research project trying to help Vodafone understand how their call centre staff shared information. When debriefing, I showed two images to explain that life is messy, and not as neat as when your brain post-rationalizes experiences.

Of all the things we need to deal with in life, relationships with other people are the most complicated and messy. All the way from marriages to initial introductions. They involve the deepest of human emotions, from who we see ourselves as, how we project ourselves to others, what we desire, who we want to become, the groups we feel a part of, who and how we love, how we think about mortality. No wonder that social design is hard.

There is a deep dichotomy between this messy reality and software builders’ desire for structured data. Maybe someday we’ll figure out that our brain is all nodes and links, deep and shallow pathways between objects, and we can directly map to it with software. But likely not in our lifetime.

I believe that one reason behind the rise of WhatsApp is that it solves the “Circles” problem in a way that embraces the idea that life is messy. Whilst Circles, and indeed Facebook Lists and Facebook Groups, all assume that the group is the defining object, with clear boundaries, WhatsApp does not. Much of WhatsApp usage is group conversations but the subtle, critical difference is that these groups are typically not permanent or sustaining. It is not a stable set of people discussing multiple things in sequence over time. It is one-off combinations of people grouped together for something temporal, like an event, a concert, a party, a weekend away. The groups then decay gracefully. When necessary they are rebuilt from scratch. Often there is a defining event that brings a group of people together, people are added, they communicate, share content, it gets messy, but then it dies.

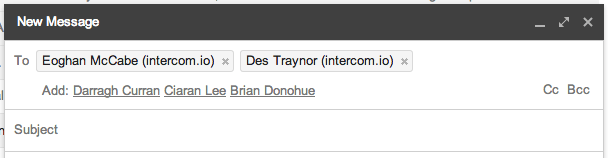

In this sense, email works the same way as WhatApp. We email the same groups of people over and over again, rebuilding the same list manually every single time. To many engineers, this is crazy, leading to horrible inefficiencies in data processing and storage. Duplication everywhere. But this is the messy reality. The cognitive effort to add in people’s email addresses is low. So doing it over and over again makes sense. Suggesting others to add based on common patterns (like Gmail does) makes this faster for people, reduces the effort, and makes it a better experience.

One wonders whether this is how Circles should have worked, or more importantly, how it should work in the future. Circles as temporary rather than permanent.

5. A fast follow product strategy doesn’t work when you have network effects

There is a nightclub close to our office. It’s pretty run down, it plays questionable music, it serves questionable beer. And it’s packed every night. People love it. Many new nightclubs have opened up next door, only to close their doors months later. They had better decor, better music, better beer. But they didn’t have the one thing necessary for success: people’s friends. People want to be where their friends are, and this trumps everything.

Google+ applied a fast follow product strategy. The theory of fast follow is to copy a competitors features, emulate the core offering, and then outperform on one other area, bypassing the incumbent product. The objectively better product wins. There are many successful examples of this strategy, including Android, Windows, Google search. For Google+, it is clear that many parts of Facebook were emulated: the Stream, Photos, User Profiles, Company Profiles, Notifications. But the one thing that couldn’t be emulated was people’s friends.

Network effects take time to build. This requires an entirely different product strategy than fast follow. And it requires patience and focus.

6. Google+ suffered shiny object syndrome

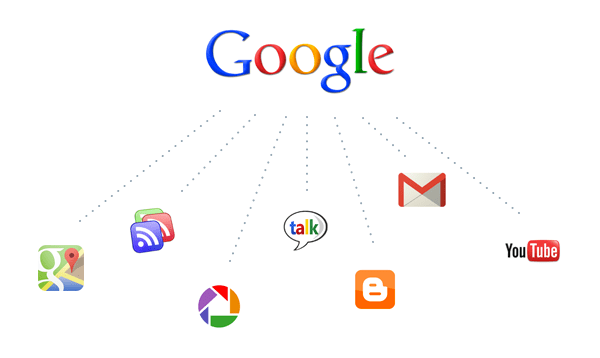

Looking back, Google had an arsenal of social products prior to Google+. The list is an incredible lineup (and I’m not the first to point this out).

Gmail: Asynchronous messaging, inline multimedia support

G Chat: Synchronous messaging, text and video

Picasa: Photos and Videos with inbuilt private sharing

YouTube: Videos with a public audience and community

Reader: Magazines

Blogger: Longer form publishing and journaling

Voice: Voice calls and SMS

I’m sure there was a ton of legacy to deal with here, but you have to wonder about what might have been if an identity layer had simply been applied across all these products and they were invested in. The same way Google applied a consistent visual design across all its products. The incredible irony is that Facebook is currently unbundling it’s apps into distinct functions with a common identity layer. Google+ didn’t necessarily need a Newsfeed for example, and it certainly didn’t need to look or be structured like Facebook. And to put the elephant in the room to bed, Google didn’t need real names, they simply needed one common way to refer to individual people. Most of the rest of the world still use email addresses to accomplish this, another irony for people working on Gmail.

7. People need clear conceptual models that exist in real life

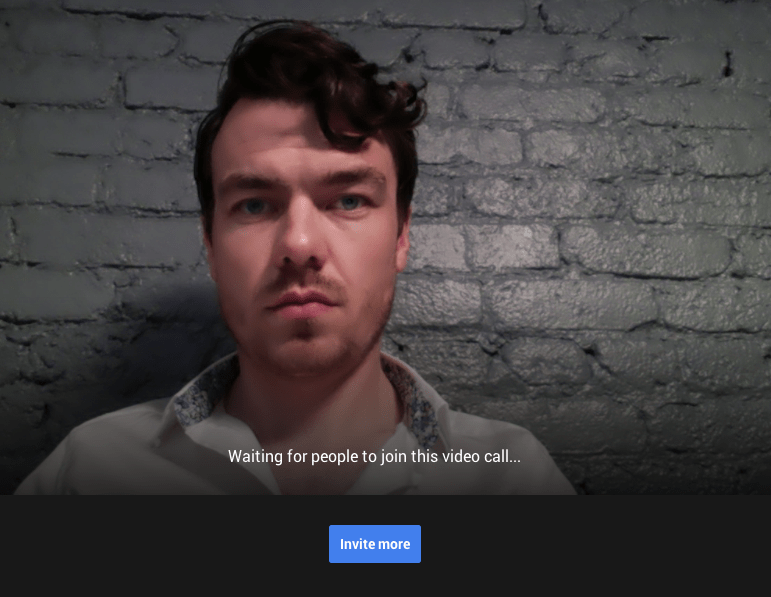

Many of our friends aren’t punctual. I remember a time before mobile phones where we had to wait at a pre-arranged meeting spot, and then wonder and wonder how late our friends were going to be. One of the best things about mobile phones was that those experiences went away. Yet Hangouts brings that experience back. Should I just wait? Should I open a new tab and do other things?

It feels broken to have to use another channel, like email or a messaging app, to talk to someone who is supposed to have joined the Hangout. The move from Google Chat to Hangouts is an interesting one. I’d love to see normalised engagement numbers on Gchat versus Hangouts, and Gchat IM conversations versus the current Hangout oriented implementation of chatting in Gmail. I wonder how successful Hangouts really is? It’s Play store rating is 3.8. I personally find the conceptual model behind Hangouts confusing and much preferred the simplicity of Gchat. I know many others feel the same.

Looking back at the history of communication, most successful social software has an analogous offline experience. Even something like a Newsfeed can be easily compared to a local town square as the primary source of news and gossip. With a new tool, people need an established way of thinking about it to reduce the perceived effort of use. I can only think of one real life experience with the same conceptual model as Hangouts – where one person puts themselves out into a place without pre-arrangement and waits for someone to join them – and it’s illegal in almost every country. It seems that to set up a Hangout, you first have to do other work, like ask someone if they are available, or create a calendar event, or at best deal with an awkward social metaphor and new abstraction: ’the hangout’.

The concept of calling someone just seems so much simpler. Hangouts are possibly great for work and meetings, not so much for calling your family and friends.

8. Distribution often trumps product

Not withstanding these issues it’s entirely plausible that Google+ succeeded in this first wave of its life. If the goal was to get hundreds of millions of people signed in to Google every day then it looks like it achieved that. Whether knowingly or unknowingly, an order of magnitude more people are now signed in under one identity, searching, emailing, watching videos. Once you have distribution, and Google have that in spades with Android, Chrome, and Search, there are many paths to success.

So what to do next?

What would one do if we applied these lessons to figure out what to do next? I think Google+ is actually in a reasonable spot. It just needs to go back to absolute fundamentals and have ruthless focus. Remember that product strategy means saying no. To understand what people problems Google+ might solve, focus on a tiny number of these, possibly even just one, and make this simple to understand, just as Instagram, Snapchat, WhatsApp, Secret have done.

Google+ is incredibly complex and hard to understand. Simplify the product offering by killing features, and lowering the effort required to get value out of it by killing many of the choices in the UI.

Finally, and most importantly, it needs to build upon established real world social norms and conceptual models. We’re still only getting started with social software. Whilst social science patterns are very well established, there are no established ways to build social products. Copying competitors is unnecessary. There are so many things we can make better for people if we carefully and deliberately observe and understand their world.