Jasmine Friedl on design, diversity and forging a different path for herself

Why should we care about diversity? Because if we are to truly design for people of all life stories and experiences, there simply is no other option.

Jasmine Friedl, Intercom’s Director of Product Design, grew up in one of the most niche environments one could imagine: the daughter of homeschoolers in northern Wisconsin. At various points, she attended a Mennonite school, then a conservative Christian high school where her graduating class was just 16 students strong. Most of the female role models in her orbit were either teachers or stay-at-home moms. With International Women’s Day approaching, we caught up with her to hear her journey from church to tech.

Initially, and not unsurprisingly, she imagined her own career might be focused on raising children at home, but after an interest in mechanical engineering morphed into one in art, she decided to press pause. She landed at Facebook in a product design role within a year of earning her MFA from the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. After stints at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative and Udacity, she found her way to Intercom. And all along the way, she has broadened her view of the world and prioritized working with talented professionals who have different creeds, origins, and experiences than her own.

I caught up with Jasmine for a chat that ranged from how she got her first big break to how she has tackled the tough task of building out her design team at Intercom from scratch.

Short on time? Here are five quick takeaways:

- Jasmine’s fascinating career in some ways began at her tiny high school – a broad generalist approach to learning helped Jasmine make the leap to product design – but growing up she didn’t see a future role for herself in anything other than teaching or homemaking.

- Tech has enabled a kind of access to people and things that wasn’t possible 20 years ago. Jasmine argues that we should use that access to connect with people in meaningful moments. Building the Safety Check feature at Facebook has been one of her most meaningful projects to date.

- When she joined Intercom, most of Jasmine’s team left (through no fault of her own)! That gave her the challenging freedom to build her own crew from the ground up.

- When it comes to diversity, Jasmine’s philosophy is equality through equity. “When I look at design, it’s about having different perspectives,” she says.

- In tech, it’s easy for a small team of designers to make decisions that affect millions of people – or billions, in the case of Jasmine’s time at Facebook. At that kind of scale, it’s essential to conduct user research that steps back from the designer’s narrow experience and asks, “What about other people?”

If you enjoy the conversation, check out more episodes of our podcast. You can subscribe on iTunes, stream on Spotify or grab the RSS feed in your player of choice. What follows is a lightly edited transcript of the episode.

Dee Reddy: Jasmine, thank you so much for joining us today on Inside Intercom. We’re delighted to have you on the show today. You’re Intercom’s director of design. But before we dive into the amazing work that you’ve done here over the past year and a bit, can you give us a bit of background on yourself and how your career has unfolded to date?

Jasmine Friedl: Thanks for having me. I’m super excited to have this conversation. So how my career unfolded. Where shall we start?

Dee: Where to start indeed? Because it’s such an interesting career trajectory. Let’s go back to the beginning.

Jasmine: Okay, let’s do it. So I’ve been actually digging into how I got where I am a lot lately, because I’ve been thinking about purpose and what it means to be a leader and what my impact on the world is. When I think about how I got into design, I actually go back to the early, early days of how I grew up. The short story is I grew up sort of dancing at poverty level in northern Wisconsin, and my mom and dad were hippies. I was born in the late ’70s – I’ll give you that and then you can calculate my age if that’s what you wanted.

“The only role models I saw for female professionals were teachers”

My parents were super, super religious. My mom was a stay-at-home mom, and my dad ended up having a lot of jobs over the course of my growing up. I was homeschooled for my kindergarten year, but my first school experience was actually in a Mennonite school. That’s a very, very conservative branch, segregated from the technology in the world, featuring very peaceful servitude.

The only role models I saw for female professionals were teachers. And I didn’t really know, going into school, what I wanted to get into. Then for junior high and high school, I was in a pretty conservative Christian school. And any patriarchal school is usually pretty small, and so I had 16 kids in my graduating class, which is not a lot. It’s not the typical high school experience. It was cool because I got to be valedictorian. When you’re out of 16, it’s not hard to rise to the top.

Dee: You should just tell people you were valedictorian. Leave out the 16 people.

Jasmine: I want to put it on a business card. The funny thing was I was actually not the only valedictorian. My best friend and I were co-valedictorians, so that brings it down a notch.

Dee: Pretty rough on the other 13 people.

Jasmine: Yeah, if you weren’t salutatorian or valedictorian… But what I found from that experience was I could pretty much be just good at anything, I could experience anything. I got to play basketball, I got to play volleyball. I was the stage manager for our drama productions. We had a math club. I really got exposure and experience to all of these things, because it wasn’t limited by needing to be qualified. They basically just needed butts in seats.

From engineering to art

Dee: Yeah, but obviously you had to have a natural desire to involve yourself in these things, as well.

Jasmine: It was also just a lot of ability to dabble, and I found that interesting as I got through my career, because the way I ended up getting into, not product design, but graphic design, was when I went to college, I ended up having the same approach. I went in undeclared, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to do.

Jasmine: My older brother had gone off to another university to do mechanical engineering, and so I was like: ”Well, I guess I’m good at math. I should be a mechanical engineer too.” And I ended up going into college, and I enrolled in some science courses. I had gotten through Calculus I and then Calculus II, but I found calculus hard so I thought: “Hmm, I want to dabble in something else. I want to take an art class.” And it wasn’t any sort of refined class; our art teacher was like my volleyball coach or something like that, so it wasn’t like my artistic skills were really developing. But I had them ingrained in me from my mom and my grandma, who had done crafts with us all the time. I like getting my hands dirty.

My advisor said: “It’s really hard to get into these art classes. You have to enroll in a major.” And I was like, “Cool, sign me up.” So I enrolled in graphic design coming out of science, and calculus, and my core classes, and I also taking ancient Greek at the time – I have two years of the ancient Greek language in my background, which I also find very strange now. I’m like, “What was I going to do with that?”

This decision ended up having me shift, because I had to apply to a program, I had to extend my college experience a year, and I had to go all-in and take all art courses to qualify for the program and then go through a review. And it ended up being that, within my broad, generalist approach in education, I made a haphazard decision to jump in and say, “I’m going to do this,” and forsake the rest, knowing I could always come back out and do something else. And I got in, and I loved it, and I was good at it. That was my entry into this world of product design in the late ’90s.

“I figured out how to do UX design without any resources and without any guidance”

Dee: And at what point when you were doing the course did it click with you that you really loved this, that you wanted to make a career out of it?

Jasmine: Even through all of my undergrad, I really didn’t have a strong perspective on this as a career. I was engaged to somebody back in undergrad, and I thought actually that my job was going to be a stay-at-home mom. I wanted to get a job, work for a couple of years, have babies and be a mom and let him work. And again, that was what was modeled for me – that was what I was set up to do, and that was the expectation that was given to me in the world I was in. And so I didn’t even process even in my early 20s that I could have something else or that I could have influence or impact on people in the world in another way.

Dee: It’s so interesting. You’re almost like the Dolly Parton of tech where you were brought up in this poor but traditional background, and you probably had molded your world in a certain way, and then at some point you just turned your back on it and have this completely different life and existence.

Jasmine: Oh, I’ll take that!

Dee: So let’s jump forward a little bit to your grad school experience. I know you told me before that your digital thesis opened up so many doors for you later on, but you only did a digital thesis because it was too expensive to print stuff for your graphic design course. Is that right?

Jasmine: Yes, it is. I did this grad program at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco. I had moved out here, and I was working in management. I hadn’t worked in design, and I wanted to refresh on design when I saw my job not going anywhere in my late 20s. I was in a graphic design program. We were constantly buying expensive paper and inks. I had my own printer that printed something like 42-inch wide paper, and you could put a roll on it, in my tiny San Francisco apartment, which is crazy. It would cost hundreds to thousands of dollars to bind books, so I tried to do them myself. I didn’t have a lot of money. I was working and doing grad school full-time. And the reason I was working full-time was because rent in San Francisco is super expensive and I needed to be able to pay that. The money I was bringing in wasn’t even covering my rent, and I needed to take out loans for the rest.

“The thing I learned about myself at Facebook was that I could get excited about just about anything”

I was really conscious of how far I was putting myself in debt, and the program was quoted to me at two and a half years, but it ended up being four years. That’s an extra one and a half years of cost that I wasn’t looking forward to. Towards the end of it, I was broken in so many ways that I had to think really strategically about how I could get through this without spending the thousands of dollars I would need to spend to have books bound. There were students in the program who would go to their thesis reviews, and they would have done a theme for their thesis, and they would have all this packaging with and full books and posters that were twice your size. All this stuff that just costs so much money, and many of them were supported by their parents. No big deal. Good for them – they got to have that experience. But I needed to do this on a budget.

So when I was looking at my thesis project, I was looking at how to help millennials manage their spending. It was something I was personally going through, and oddly enough, it played very much into the first real product designer job I had, which was working on payments at Facebook. It was a space that I was really interested in, and I thought: “I can do an app. I can design an app. An app does not require printing. It does not require any books or posters.” So I figured out how to do UX design without any resources and without any guidance. And I have to tell you: looking back on it now, it’s embarrassing.

Finding purpose at Facebook

Dee: I mean, that informed and led to your UX experience. As you mentioned, you worked for Facebook for four years. Let’s talk about your time there, because you were involved in some really fascinating projects. You mentioned payments in Messenger. I know you also worked on Safety Check on Summit Public Schools. What sticks out for you as a really, really exciting project to have been involved in?

Jasmine: The thing I learned about myself at Facebook was that I could get excited about just about anything. I could find a meaning behind it. And so when you look at payments at Facebook, it’s financial, and it’s dry, and it’s not the thing that makes people say, “I want to work at Facebook, and I want to work on that.” They usually want to work on Messenger or something consumer-facing and forward and edgy. And I found that really interesting, because we were solving a problem, and the problem isn’t as evident to us who are in the first world. It’s more evident to those who are in the third world in that we were enabling people who had small independent businesses in places like Jakarta or Delhi to be able to sustain their business through Facebook, through advertising and selling their goods. I found that really fascinating when normally I’d be like, “Oh, okay, cool. Somebody else can do that.”

Dee: Well, you’re actually democratizing financial services for people, which is an extraordinary thing to be involved in.

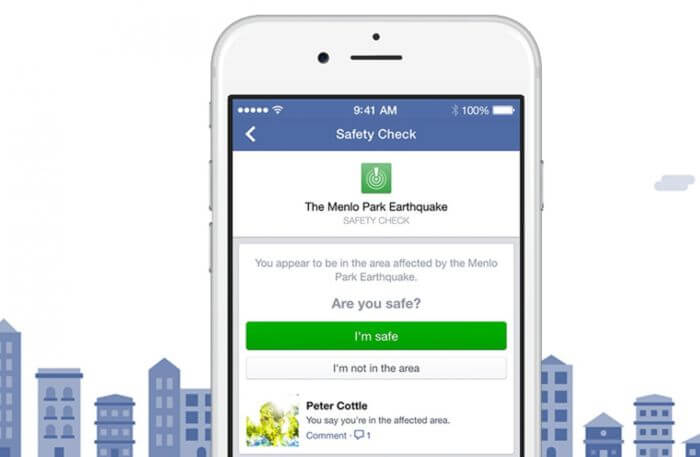

Jasmine: Absolutely. And in fact, I did the payments in Messenger, which is still running. But as far as looking back and saying, “What was the special moment that I had at Facebook?” It definitely was the Safety Check project. It’s also still up and running. That’s the one where, if you’re in an area that there is a natural disaster or some sort of crisis, you can mark yourself safe and then alert your friends and family that you’re okay. It gives peace to people who are connected to you in some really dire situations.

Dee: It’s such a fascinating one – one that probably needs no introduction, because it’s one of the more iconic features in Facebook. How did that spark of inspiration come to you for that?

Jasmine: This was from an engineer, Peter Cottle, who had noticed during the Boston Marathon bombings that people were using Facebook to be able to tell each other that they were safe. And so he went through a hackathon and designed a megaphone. It was just a banner at the top of the page that says, “I’m safe.” He was on a different team, but he had been working with one of the PMs who was on payments growth. She came to me and asked, “What do you think about this?” And I said: ”Holy crap, we need to work on this. This is not just a banner that you check, this is an experience. This is something that people are going through. This is very emotionally and anxiety driven. We really have to think through the experience.”

I’ve worked in education, and I will say that’s some pretty meaningful work. The challenge with education is you don’t see results immediately. You build something wonderful on a platform, but it takes years for you to see the results of students. Did the platform or the learning style affect people’s lives? Well, you don’t know until they get through high school or through college. There’s an eight year span on working with high school students to see if your work is successful.

With Safety Check, on the other hand, we saw immediately the effect of it, and it was outstandingly positive, especially for all of the stuff that Facebook has gone through lately. It was really special that we were able to actually look at natural behaviors on Facebook and create a lot of good for the world.

Dee: I do think it has a good impact on the world. I’d give the example of the Bataclan incident in France. That was the first time I became aware of it. I realized, “Oh gosh, I actually know 15 to 20 people that are in Paris or live in Paris.” Whereas if I had heard that on the news, I don’t know that it would have resonated as much with me how close that was to my life. It’s really important for people to be able to connect with world events like that and understand how far-reaching they are.

“We have access to things and people that we didn’t have 20 years ago, and using that access for good isn’t just about connecting with anyone, it’s about connecting with people in meaningful moments”

Jasmine: At the time, Facebook’s mission was all about making the world more open and connected. What you’re saying was so in line with our mission. The world with technology has gotten so much smaller. We have access to things and people that we didn’t have 20 years ago, and using that access for good isn’t just about connecting with anyone, it’s about connecting with people in meaningful moments. That’s really powerful.

Moving to Intercom

Dee: Let’s chat a bit more about your move to Intercom. You’ve said before that it was a quick but thoughtful decision. What was it about Intercom that made you so able to make that decision quickly?

Jasmine: It was funny. I went out and found Intercom; Intercom didn’t find me. When I decided it was time for me to move on from Udacity, I knew that I had some space to be intentional about what I wanted and what I didn’t want. I was looking on Glassdoor, I saw the role, and the way it was written, I thought: “That’s me. You need me.” And I had done the same thing for Udacity. I was like: “Somebody needs to come in and lead in SF and build out a team and write about design and product. Oh, this is all the stuff that I do.”

Emmet Connolly, Intercom’s Senior Director of Product Design, who covers the Dublin and London teams, had actually reached out to my husband (who’s also a product designer) about the principal design role we had in San Francisco. My husband connected me with Emmett who was in town from Dublin with Paul Adams (SVP of Product). They just said to come on down and do an interview. I don’t think I was quite ready. I was still getting a portfolio together and thinking about what I wanted. There wasn’t a lot of preparation, and I know there were a lot of other fantastic candidates in the pool, too.

We deeply connected. I can’t describe how that room felt, but I felt I was understood. I felt we were talking about the right things. I felt like I was having fun. Interviews can go a lot of different ways. It wasn’t just good interview etiquette that I was using or they were using. It was something better than that. It was special. I walked away after an incredibly long interview, and I was exhausted. I was heading to wine country with some girlfriends that night, and I called my husband on the drive over and said, “Hey, this is something special.”

We talked strategy, and we talked through what would be right for me and what would be right for us. That was on a Friday. On Tuesday, I got an email from Paul that was like: “This is it. We could build some really great things together.” The sentiment he gave me in his email was exactly what I was feeling. I obviously have a lot to learn, but I developed a lot of the precise skills that this organization and this team needed. And boy, oh boy, have we seen those tested this past year. But it was the right blend of qualifications plus the right blend of people plus something magical.

Putting people before product

Dee: How have you gone about building and structuring your team here at Intercom?

Jasmine: Yeah, that’s been a year’s worth of work. When I came in, I started off with four folks who were here. Previously, I had a team of 20, and I was managing all of the designers and design systems, having dotted lines to brand and also handling design program management and research. I had a pretty big scope, and this felt really tight and manageable. The short story is that every single one of my teammates left. It wasn’t because of me; I came in, and they were like, “See you later.” Each of them had very specific individual reasons they needed or wanted to go. One was a contractor and didn’t want to go full time. One wanted to move back to San Diego. At this point, we don’t offer remote work.

As we went through those career conversations, as one does when they join a team, we said: “Hey, I’m here. I’m invested in you. Where do you want to go?” And that ended up being, “Not at Intercom.” My goal as a people leader is always to put people before product, because I believe firmly that people are how you get the great product. In supporting each one of them through their transitions, I just had to let them all go. “Spread your wings, and go where you’re going to be great.” Over time, that left me having to hire up an entirely new team.

That’s what I’ve been doing this past year. The great news is I now have everybody I needed. It was definitely hard, because I had to refashion all of my priorities to do this. I had to do things like rewrite an interviewing process that I felt was more open to bringing the right kind of people in. I had to reshape our mini-organization and determine what roles we needed. Something I introduced was the idea of a manager for our team so that I could play the director role. Then we did a lot of recruiting and a lot of interviewing. Since my team was new, the first person I ended up bringing in was actually somebody I had worked with before at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

“I have designers that complement each other… they work well together and they get along and they support each other. It’s something, again, that feels pretty special and magical”

I didn’t steal her from Chan Zuckerberg. She had quit, and then we had lunch, and she ended up deciding to go through the process and was my first hire. She of course had to start interviewing her new teammates. Within two weeks she was interviewing with me, and it was a blessing, because we had done interviewing together before. But we have now built up the team, and because of it as a byproduct, we actually have better interviewing processes that we’ve scaled to our global design team. We’ve done a lot of things on the recruiting side that have served very useful, just for building up a pipeline when we open new roles.

For example, we opened another role this year just in January for another product designer and we filled it in 22 days – which is some kind of record – because of all the work we had done to invest in the community and bring folks in and get them familiar with Intercom. The anxiety and the stress it caused me was enormous. But there was also a silver lining in that I got to actually intentionally look at what I wanted the team for product design to be. I have that team now. You don’t always get that. Sometimes it’s one in, one out. But here, it was from scratch. And I have exceptional designers, really some of the best that I’ve seen.

“Why is diversity so important to me? It has to be”

I have designers that complement each other. And when we think of the shape of our team, I never want to bring in too many people at the same level or with the same skill set. We want to create spaces and opportunities for them to grow their competencies and to have experiences where they can mentor each other. I’m super pleased not only that they’re good designers and that they perform really well, but that they work well together and they get along and they support each other. It’s something, again, that feels pretty special and magical.

From skirts to suits

Dee: And one thing that you’ve been really strong on throughout your career and I suppose it’s reflected in your recruitment process, is diversity and inclusion. Why is this so important to you?

Jasmine: Why is it so important to me? It has to be.

It’s funny, because I do now, but I never thought about myself as a feminist. It comes back to that religious background. The idea that women are secondary, that men are leaders of the family and that women support men. There are lines in marriage vows that say women must obey their husbands, and that can be either interpreted as a little bit antiquated, or just how it is.

“The word ‘feminist’ used to make me really, really uncomfortable – probably because of some of the religious themes in my upbringing”

Dee: Yeah, we ditched that line a good few years ago over here.

Jasmine: Yeah. And there are some churches that still subscribe to it, and whether you say it or not, it makes me uncomfortable. But it didn’t 15 years ago. I’d think: “Cool. I understand what that means. I understand what model this fits under.”

The word “feminist” used to make me really, really uncomfortable – probably because of some of the religious themes in my upbringing. But I noticed that, even in my management job where I was for six years, I was always the most excited when I could support females and promote them to management roles. I was excited for myself when I started to move forward in my career. I had some underlying purpose of helping women succeed, because I was starting to discover that I could, too. I don’t think I had words around it or concrete thoughts about it, but I can see that now. So when I did my thesis project and was thinking about the topic I wanted to explore, one of the things I looked at was this idea of equality. I had written a book just for me to explore the topic, and I called it “Skirts to Suits”.

Dee: I love that title.

Jasmine: I liked it, too. And it was about this progression from early feminism and getting the right to vote to where we are now: trying to get ahead of business and just constantly seeing that role given to somebody who goes out for beers with his boss. That was the culture of the job I was coming from, but let’s be real: that is the culture that we’re still living in.

Dee: But there is a push more nowadays – rather than forcing women to conform to the suit – to actually make space for the skirts in the workplace. That’s a messy, messy analogy. But you get what I mean that to embrace femininity in the workplace more than assuming that it should be something that weighs you down.

“I firmly believe that if we don’t expose some of the uncomfortable edges of ourselves, we don’t give space for other people to feel comfortable with those edges and therefore be honest about them or expose them themselves”

Jasmine: Yeah. For a while – and still in many places – you had to fit a certain mold, even if you were female. I did that; I wore pantsuits to work for six years, and now we’re at a better place where we say: “What about authenticity? What does it mean to be able to bring your authentic self to work? What does it mean to be an authentic leader?” And we’ve had to go through some really terrible things. I think of #MeToo as a movement that forced us to have some deep and dirty discussions to be able to get here. I don’t know that we’re in a good place, but we’re making progress. And when I look at how I lead, I am probably a far-too-vulnerable, far-too-transparent leader at times. I’m rough, and I’m rugged, and I’m raw around the edges. I say the wrong thing all the time, but it’s under the intent of authenticity, because I firmly believe that if we don’t expose some of the uncomfortable edges of ourselves, we don’t give space for other people to feel comfortable with those edges and therefore be honest about them or expose them themselves.

So it’s one of the reasons why, when I talk about my past, I’m like, “Let’s just get into it.” There’s nothing I have to hide. There are things that might be embarrassing. If it’s not going to hurt me – and hopefully hurt other people – then I’m open to it. And I’m always down to talk about just about anything because we can do better with our authenticity. Allowing people to be themselves is just one of a lot of other things that we need to do to enable more diversity and more inclusion.

Dee: Which is a dream from my perspective, to be perfectly honest with you. But it’s really timely to be having this discussion, because we’re releasing this episode the week of International Women’s Day. From a design perspective, I’m really curious: what’s the impact of having more diversity in the groups of people that are actually designing?

Jasmine: When I came into Facebook, we were launching Facebook Home, which basically came on the HTC One phone and some other Androids. Facebook was your home screen. And I remember looking at the design team launching it and seeing three blonde, white, male designers. At that point I didn’t really think much about it. But now I’m like, “Where were the senior principal level female designers?” They just didn’t exist. And it’s not to say that that had anything to do with the success of the project.

“When I look at design it’s about having exactly what you said: different perspectives. And that could be through different backgrounds, or it just could be fruit from different experience backgrounds”

When we think about diversity, there are so many different kinds of diversity. Some of it is like – I guess I was going to say the right kind, but I don’t want to put judgment on this. We obviously want to bring in people from different ethnic backgrounds and genders and be able to get experience through that. The thing I worry about is when we are just chasing numbers rather than chasing outcomes. And we’re looking at a place where we want to have true equality through equity, and equity means bringing people up so that we have a level playing field. And so when we talk about recruiting and hiring, we often talk about numbers. But I fear that, especially the tech industry, we are just trying to pull people of color from comfortable places to reach those numbers. And really what we need to do is groom and enable people who wouldn’t normally have opportunity to have opportunity and work towards that equality through equity. When I look at design it’s about having exactly what you said: different perspectives. And that could be through different backgrounds, or it just could be fruit from different experience backgrounds.

Dee: Exactly. Or even your experience of not being able to afford printing when you were in college.

Jasmine: And we could spin that in a way where every white male could say: “Well I have this. Nobody went through this.” And we want to use that to still diversify our perspective. But there are places where we’re doing great. I look at the London design team at Intercom and the six or seven designers there are from six or seven different countries. That brings in different perspectives. And when I look at my team, we’re 50% women. I’ve got two designers from China, and they ended up having big experiences in their lives in different parts of the world, right?

But there’s also things that we need to consider, and I loved working at Chan Zuckerberg Initiative because of this. We can think of different sexual orientations. That’s one that we obviously don’t want to expose in the interviewing process if the candidate doesn’t wish to, because that can go wrong in places that aren’t looking for diversity and inclusion. But another thing we talked about at CZI was there are a lot of liberal Democrats working at CZI, because we’re in California and because we’re pretty progressive in how we think about education and healthcare and things like that.

And they wanted to hire Republicans. It seems strange, but we actually have to have that balance in order to have that debate. When we have that diversity of experience and perspective and a balanced conversation, we can’t just bring people in and say, “Oh, you come from here, but now do this the way that I want you to do it.” We have to actually encourage dialogue to inform the work we do in order to have better solutions.

Some of the best examples of this are from Facebook, where we were designing for billions of people. You’d get a designer who had an idea and they’re like: “I want it this way. I believe that we should do this, because I feel this.” And it’s very egocentric. You’re like: “Well, that’s cool, but have you checked with our millions of users in India? How do they feel? What do they need?” User research became a really important part of our product organization at Facebook while I was there. It went from a handful of researchers to hundreds, because we needed support in understanding different perspectives. And the reality is even the most diverse design team can’t do it alone. We still need to use data and research to inform our opinions. But that’s advice I give a lot. I say: “Okay, cool. Now what? What about other people?”

“I continually look back to those women and this week is an especially great time to celebrate them, because they are the people who are blazing the path for folks like me”

Dee: Before we finish up, Jasmine, we’d love to know is there a business or design leader who inspires you in the work that you do?

Jasmine: When I look at who I’ve been able to work for, I am so lucky to have the caliber of leaders I’ve had. Paul, my boss, is phenomenal and one of the best people I’ve worked for. When I look at who has pushed me the furthest in my career, I actually have two female leaders that I feel so lucky to have worked for. At Facebook I had three female managers and three males. I also understand that this isn’t normal, but I worked for Maria Giudice who was also our CEO at Hot Studio and came over to Facebook when we were acquired. She was a direct manager of mine, and I also worked for Margaret Stewart. And when I credit who has helped me get to where I am and who has helped me really learn about myself and become the authentic leader I am now (while also understanding that I have a long way to go), it’s those two women.

Maria is the most authentic person I know. She’s weird, and she’s awesome, because she’s so true to herself. She’s vulnerable, and she’s driven, and she actually wrote a book called The Rise of the DEO when she was doing her business, which is about the design executive officer. I’ve been so close to her, and she’s become a friend and a mentor over time, as well as a leader. And I want to embrace that authenticity.

And then when I look at Margaret Stewart, who’s a VP of Design at Facebook, she’s working on some really tough stuff right now. And she knows she needs to be there, because she cares deeply about the world, and she cares deeply about the company doing good in the world. And she is not only a wonderful, lovely human, she’s also just so committed. And when I look at that tenacity and that drive she has – while still being a funny and warm and lovely human – I have so much to learn from that. Because when we go back to my purpose, tenacity is not necessarily something I had. I had this go-with-the-flow attitude, and I’ve had to develop that over time to be fierce like she is fierce. I continually look back to those women when I want to look at a role model for who I want to be.

This week is an especially great time to celebrate them, because they are the people who are blazing the path for folks like me. And I hope I can do that for others who follow me as well.

Dee: Well, I think you certainly are. So before we let you go, Jasmine, where can people keep up with your work?

Jasmine: Let’s see, probably Twitter: I’m @jazzy33CA, for California. I go on and off, but that’s where you can find me. My husband and I have a podcast called New Layer. You can find it where any podcasts are found. We have very casual, cool discussions – kind of like we’ve had, Dee – and we talk about a lot of stuff that product designers in their career struggle early in their careers. Everything from “How do I interview?” to “How do I do a whiteboard exercise?” to “How do you work with engineering?” We’ve got a year’s worth of work up there, and we will continue to do that weekly, until we need a break.

Dee: Fantastic. Thank you so much for joining us today, Jasmine. It’s been a real pleasure.

A note about our artwork. To further celebrate International Women’s Day and support the work of female designers, we asked Jasmine to recommend an artist who she admired. Christina Chung is a Taiwanese-Hongkonger-American illustrator who creates intricate, symbolic illustrations that celebrate diversity and the power of storytelling. You can find out more about Christina and her work here.